Natural disasters such as hurricanes often exacerbate pre-existing environmental issues in environmentally vulnerable communities; however, many may argue that the consequences that follow the disaster are the result of an unnatural societal issue in which the inequalities that exist in minority and low-income neighborhoods are ignored. As Michael Eric Dyson puts it, the occurrence of a natural disaster provides the space for us to blame pre-existing inequalities on a disaster that was not caused by human actions, but rather is an “act of God.” Instead of recognizing that poor and minority communities have “been abandoned by society and its institutions,” we find the space to place all of the blame on the natural disaster that has occurred, ignoring the fact that many of the issues that have become relevant already existed, and have been exacerbated by, rather than caused by, the disaster

On August 25, 2017 Hurricane Harvey, a category 4 hurricane, hit Texas. Harvey was the first major hurricane to hit Texas in over 40 years and, according to the National Hurricane Center, caused over $120 billion in damage. Dumping more than 27 trillion gallons of rain over Texas, Hurricane Harvey became the “wettest Atlantic hurricane ever measured.” Of the many areas affected by Hurricane Harvey, Houston, Texas bore much of the brunt of the storm. After receiving over 50 inches of rain from the hurricane, one-third of the city was completely flooded and the weight of the water caused the city to sink almost an entire inch. The floods from Hurricane Harvey forced almost 40,000 people out of their homes and into shelters. In addition to Houston, Dallas, Texas was also greatly affected by the storm. Similar to the Superdome in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, Dallas also used its convention center to provide a place for about 5,000 residents to stay after evacuating their homes. After the storm, the total damage was measured to be about 8 million cubic yards of garbage in Houston, alone.

Source:

https://www.chron.com/news/houston-weather/hurricaneharvey/article/Is-it-safe-to-drive-back-to-Houston-Harvey-12161331.php

In 2017, Houston had a population slightly over 2.31 million people. At the time of the hurricane, the population was 24.7% White, 22.5% Black, and 44.6% Hispanic or Latino. Additionally, the median income at the time was $50, 896 and about 14% of the population lived in poverty. It is important to note Houston’s role as a port city, as the city experiences a regular influx of immigrants. The Hispanic population of Houston is continuously growing as more and more immigrants move into the city to find work. According to the World Population Review, it is estimated that there are about 400,000 undocumented immigrants living in Houston. Additionally, Houston also has a relatively large refugee population (about 1600 refugees arrive in Houston each year).

When considering the lack of environmental justice after Hurricane Harvey, it is important to understand the demographics of the area. As we can see, Houston is a majority minority city. Environmental racism has existed in Houston since before Hurricane Harvey, and continues to exist today. According to Robert D. Bullard, a study concluded that African-Americans in Houston are exposed to “56 percent more pollution than is caused through their consumption of goods and services.” The same study concluded that this percentage is even higher for the Latinx population (about 63 percent). This means that African-American and Latinx populations in Houston are exposed to a significantly larger amount of pollution than the pollution that they produce. In other words, pollution produced by white populations, businesses, etc. is being dumped on to black and Latinx communities. This study demonstrates the disproportionate burden that communities of color bear regarding environmental toxins in Houston.

Environmental racism in Houston is the result of local, state, and federal policies that work against the well-being of communities of color through enforcing segregation, preventing access to affordable housing, and depriving minority communities of the resources that white communities benefit from. In addition, locally unwanted land uses (LULUs), like the many factories and refineries of industrial Houston, are often located in and around minority communities, adding to the burden of environmental toxins and pollution not caused by those living in the communities.

The disproportionate distribution of environmental burdens can cause various problems in communities of color and low-income communities. Many of these conditions were exacerbated by Hurricane Harvey as it dumped almost 30 trillion gallons of water over the city. Bullard gives a specific example of such exacerbation. When Houston was hit with such large amounts of water, several LULUs (specifically petrochemical facilities) in communities of color and low income communities were damaged. This damage led to the release of millions of pounds of harmful chemicals and pollution into the air in and near these environmentally vulnerable communities.

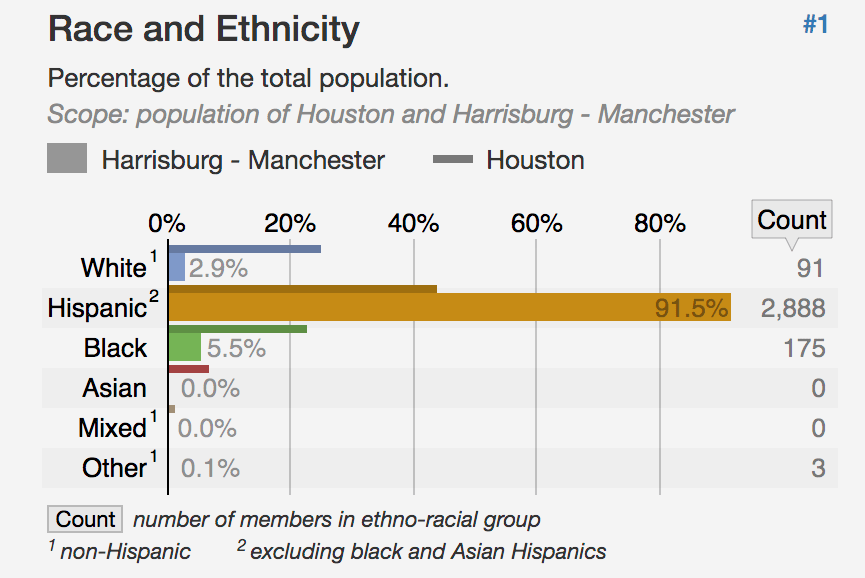

Manchester, a community in Houston is a perfect example of how pre-existing inequalities created greater issues after Hurricane Harvey. The chart below shows us that the population of Manchester is 91.5 percent Hispanic, 5.5 percent Black, and 2.9 percent White. According to Houston Public Media, “Houston is one of the most ozone-polluted cities in the country.” However, Manchester’s overall air quality is even worse. The majority minority and low-income neighborhood is surrounded by two major highways, the Houston Ship Channel, and various refineries (Goodyear and Valero are two familiar names that have refineries in/near Manchester). The location of these sites in and around Manchester is the result of environmental racism and greatly contributes to the observed inequalities and disproportionate exposure of communities of color and low wealth to toxins. In 2017, Hurricane Harvey exacerbated these conditions as its, trillions of gallons of water led to oil spills and the release of benzene, a cancer-causing chemical, into the air. Additionally, as often seen as a result of environmental racism, government responses (by the EPA and state regulators) to the issue were slow and minimal.

Source: https://statisticalatlas.com/neighborhood/Texas/Houston/Harrisburg—Manchester/Race-and-Ethnicity

Manchester is only one example of an affected community after Hurricane Harvey. With Houston being a largely industrial city, several communities experienced catastrophes similar to that of Manchester. After the storm, reporters developed a list of 100 toxins that had been released into the environment post-Harvey. These toxins existed on land, in water, and in the air. Although many of the released chemicals and carcinogens were never publicized, the known chemicals were recognized to be linked to irritation of the eyes and respiratory system, as well as to cancer. The Dallas Morning News tells us that these releases could have been avoided through simple actions taken by the refineries and other plants located in and around Houston. According to the Environmental Integrity Project, if the refineries had scheduled a planned shutdown upon understanding the warnings regarding Hurricane Harvey, the large amounts of chemical pollution could have been reduced, if not omitted. In addition, The Dallas Morning News states that the state government elected to “suspend pollution reporting requirements” after the storm, making it difficult to assess health impacts on the residents of nearby minority and low-income communities. Failure of the refineries to schedule a shutdown as well as the failure of the government to carry out the proper procedures to fully understand the environmental aftermath of Hurricane Harvey are examples of Dyson’s unnatural disaster previously mentioned. The minority and low income communities of Houston were greatly affected by the decisions made as a result of environmental racism and classism. Dyson would agree that it was these decisions that greatly harmed the residents of these communities, rather than Hurricane Harvey itself. Hurricane Harvey, an unpreventable natural disaster caused flood damage, but the other issues that existed, and continue to exist, were caused by incidental pre-existing inequalities that place environmentally hazardous LULUs in the backyards of minority and low-income people.

Source: https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2017/08/this-should-obvious-but-just-in-case-hurricanes-and-oil-country-are-a-recipe-for-disaster/

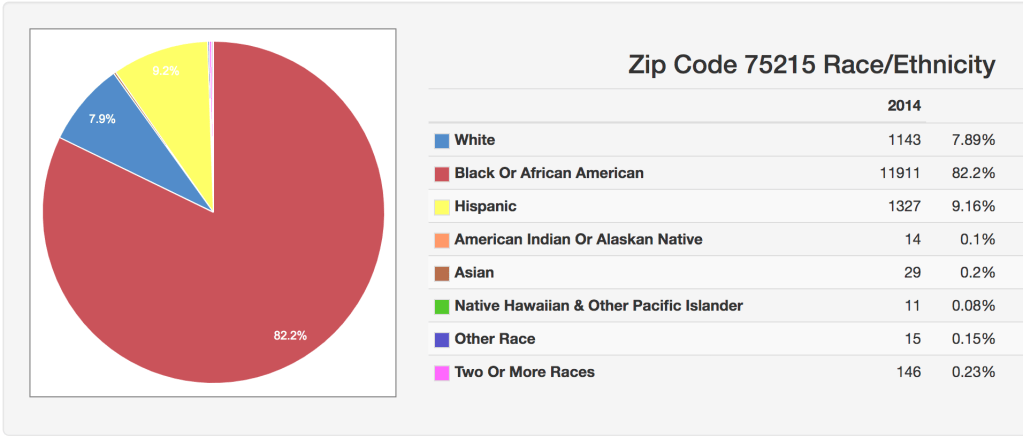

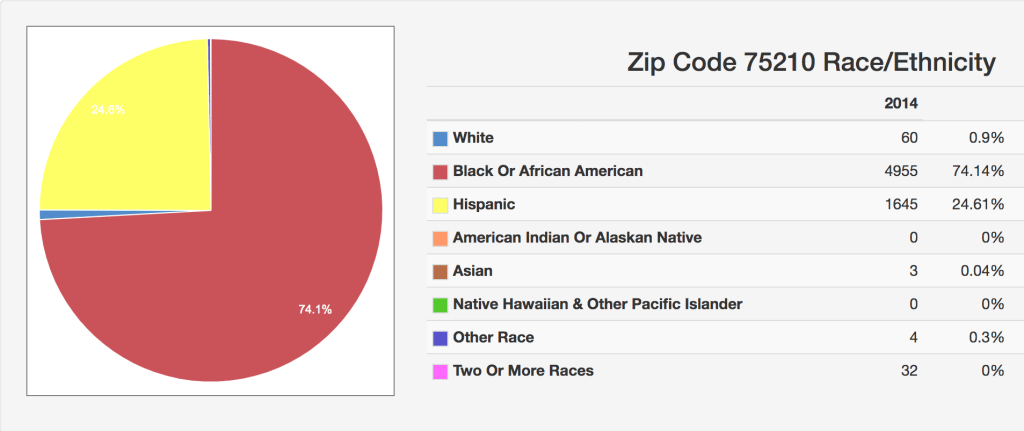

Communities in Dallas, Texas also face the disproportionate burden of environmental inequality and injustice. Aside from Hurricane Harvey, Dallas, especially South Dallas has been in a fight against unhealthy led levels. Specifically, two zip codes in South Dallas were intentionally excluded from a plan to address the lead issue that persists. According to The Dallas Morning News, these zip codes are 75215 and 75210. The graphs below show the racial distribution of these zip codes in 2014.

As we can see, these zip codes are majority minority communities. It is not unintentional that these specific communities were excluded from the plans to address the lead issue in Dallas. In addition to being majority minority, each of these communities have relatively low median household incomes ($20,240 for zip code 75215 and $18, 567 for zip code 75210). Again, we can reference Dyson’s argument that low-income and minority neighborhoods are neglected and “abandoned by society and its institutions.” Although there exists a dearth of research connecting this lead crisis to Hurricane Harvey, this example demonstrates how the decisions of law and policy makers (as well as other stakeholders, such as corporations) often disregard the well-being of low-income and minority neighborhoods. In many cases, the failure of stakeholders to consider impacts on low-income and minority neighborhoods leads to unnatural disasters that may later be exacerbated by natural disasters.

As we have seen, environmental racism exists both in Houston and Dallas. The aftermath of Hurricane Harvey connected the two cities and exacerbated issues in each. As we have discussed, Houston received much of the brunt of the storm and experienced extreme chemical exposure through land, water, and air. As mentioned earlier, the convention center in Dallas served as a shelter for those escaping the damage of the storm. Many people fled to Dallas from Houston temporarily; however, there was also a large population of people who remained in Dallas after fleeing Hurricane Harvey in Houston. According to The Dallas Morning News, Dallas attracted hundreds of people, as the city desperately needed workers of all kinds; however, the influx of people resettling in Dallas led to the strong possibility of exacerbating to the affordable housing crisis that already existed there.

With large influxes of people fleeing from Houston into Dallas, the affordable housing crisis in Dallas became quite severe. After the storm, Dallas became the go-to point for many Houston residents; however, this led to a lack of shelter in Dallas as hotels and other shelters continued to fill up. At the time, thousands of families faced the decision of returning to Houston to rebuild their demolished homes or remaining in Dallas to start fresh. This is not a new concept for Dallas, as many Hurricane Katrina evacuees fled to Dallas in 2005. A year after Hurricane Katrina, the New Orleans population size had nearly been cut in half. In 2017, the population still had not fully recovered, as studies showed that it was only about 86% of the pre-Katrina population. The largest contributor to this drastic population decline was the rate of renters compared to home-owners in New Orleans. Since many Katrina residents rented rather than owned their homes, they did not have homes to rebuild after the storm. While many New Orleans natives refused to leave their homes or did not have the means to do so, many others who were able to flee the city had very low incentive to return due to the fact that they were renters and did not have homes to rebuild. Those who did not return to New Orleans moved to other cities with less dense poverty, better schools, and better opportunities, like Dallas. In addition to Dallas, large populations of people migrated to Houston, which would later lead to more people migrating to Dallas after Hurricane Harvey, 12 years later.

As Hurricane Harvey victims continued moving from Houston into Dallas, the affordable housing crisis was exacerbated as there was no way to predict when the migrations would slow down. In addition to these large migrations of people, large, high-paying corporate companies also continued to move into Texas seeking new employees. Very few Dallas residents were looking for work, but new migrants could fill base job positions at low wages that set these corporations up for success. The problem here is that as more corporations move into Texas, more and more people are attracted to the area, but the construction and housing market could not keep up. In addition to and as a result of the construction labor shortage (partially caused by rebuilding efforts in Houston) in Dallas, building affordable houses for the people in these low-wage jobs became very difficult, and was a slow process.

Source: http://stories.kera.org/no-place/2017/05/17/why-dallas-and-other-cities-struggle-with-affordable-housing/

Hurricane Harvey was a natural disaster that was unpreventable, but the issues that came to the forefront following the disaster were unnatural and already existed. Issues of LULUs in Houston and lack of affordable housing in Dallas existed before Hurricane Harvey; however, the tons of rain that came with the Hurricane exacerbated the issues displacing low-income and minority residents who experienced the worst damage from the storm.

Works Cited

Amadeo, Kimberly. “Hurricane Harvey Shows How Climate Change Can Impact the Economy.” The Balance, The Balance, 25 June 2019, https://www.thebalance.com/hurricane-harvey-facts-damage-costs-4150087.

Atkin, Emily. “This Should Be Obvious but Just in Case: Hurricanes and Oil Country Are a Recipe for Disaster.” Mother Jones, 25 Aug. 2017, https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2017/08/this-should-obvious-but-just-in-case-hurricanes-and-oil-country-are-a-recipe-for-disaster/.

Bullard, Robert D. “Environmental Racism: It’s Real and Democratic Candidates Must Show How They’ll Address It [Opinion].” HoustonChronicle.com, Houston Chronicle, 10 Sept. 2019, https://www.houstonchronicle.com/opinion/outlook/article/Environmental-racism-It-s-real-and-Democratic-14422829.php.

Cbs. “Hurricane Harvey’s Toxic Aftermath More Impactful Than Thought.” CBS Dallas / Fort Worth, CBS Dallas / Fort Worth, 22 Mar. 2018, https://dfw.cbslocal.com/2018/03/22/hurricane-harvey-toxic-environment/.

Cowan, Jill. “As Hurricane Harvey Evacuees Make Dallas Home, What Katrina Taught Us about How D-FW May Change.” Dallas News, Dallas News, 25 Aug. 2019, https://www.dallasnews.com/news/texas/2017/10/12/as-hurricane-harvey-evacuees-make-dallas-home-what-katrina-taught-us-about-how-d-fw-may-change/.

Cowan, Jill. “As Hurricane Harvey Evacuees Make Dallas Home, What Katrina Taught Us about How D-FW May Change.” Dallas News, Dallas News, 25 Aug. 2019, https://www.dallasnews.com/news/texas/2017/10/12/as-hurricane-harvey-evacuees-make-dallas-home-what-katrina-taught-us-about-how-d-fw-may-change/.

“Houston, Texas Population 2019.” Houston, Texas Population 2019 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs), http://worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/houston-population/.

“Houston, TX.” Data USA, https://datausa.io/profile/geo/houston-tx/.

Leighton, Heather. “Is It Safe to Drive to Houston after Hurricane Harvey? Here Are the Routes That Are Still Closed.” Houston Chronicle, Houston Chronicle, 2 Sept. 2017, https://www.chron.com/news/houston-weather/hurricaneharvey/article/Is-it-safe-to-drive-back-to-Houston-Harvey-12161331.php.

Mosier, Jeff. “Impact of Hurricane Harvey on Health, Environment Still a Concern a Year Later.” Dallas News, Dallas News, 24 Aug. 2019, https://www.dallasnews.com/news/texas/2018/08/16/impact-of-hurricane-harvey-on-health-environment-still-a-concern-a-year-later/.

“Race and Ethnicity in Harrisburg – Manchester, Houston, Texas (Neighborhood).” The Demographic Statistical Atlas of the United States – Statistical Atlas, https://statisticalatlas.com/neighborhood/Texas/Houston/Harrisburg—Manchester/Race-and-Ethnicity.

Staff, World Vision. “2017 Hurricane Harvey: Facts, FAQs, and How to Help.” World Vision, 19 Aug. 2019, https://www.worldvision.org/disaster-relief-news-stories/2017-hurricane-harvey-facts.

Trovall, Elizabeth. “Along Ship Channel, Houston’s Manchester Neighborhood Grapples With Poor Air Quality.” Houston Public Media, 28 June 2018, https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/news/politics/immigration/2018/06/22/292344/along-ship-channel-houstons-manchester-neighborhood-grapples-with-poor-air-quality/.

“When Fighting a 1994 Lead Poisoning Health Crisis, City Officials Had a Plan That Ignored South Dallas.” Dallas News, 21 Nov. 2019, https://www.dallasnews.com/news/from-the-archives/2019/11/20/in-plans-to-fight-a-lead-poisoning-health-crisis-city-officials-ignored-south-dallas/.

“Why Dallas And Other Cities Struggle With Affordable Housing.” One Crisis Away: No Place To Go, 24 May 2017, http://stories.kera.org/no-place/2017/05/17/why-dallas-and-other-cities-struggle-with-affordable-housing/.

“Zip Code 75210 Profile, Map and Demographics – Updated December 2019.” Zipdatamaps.com, https://www.zipdatamaps.com/75210.

“Zip Code 75215 Profile, Map and Demographics – Updated December 2019.” Zipdatamaps.com, https://www.zipdatamaps.com/75215.