Houston: the Energy Capital (and Environmental Injustice Capital) of America?

Cancer Clusters in Houston Area:

Over the last decade, the Texas Department of State Health Services has published more than 260 cancer cluster investigations.

In 2015, one particularly groundbreaking study found that East Harris County and Houston had higher-than-average rates of cancer from 1995 to 2012. This came as no surprise to the towns’ residents, who had long reported health problems due to the presence of petrochemical plants, oil refineries, several Superfund sites, and other waste and industrial businesses.

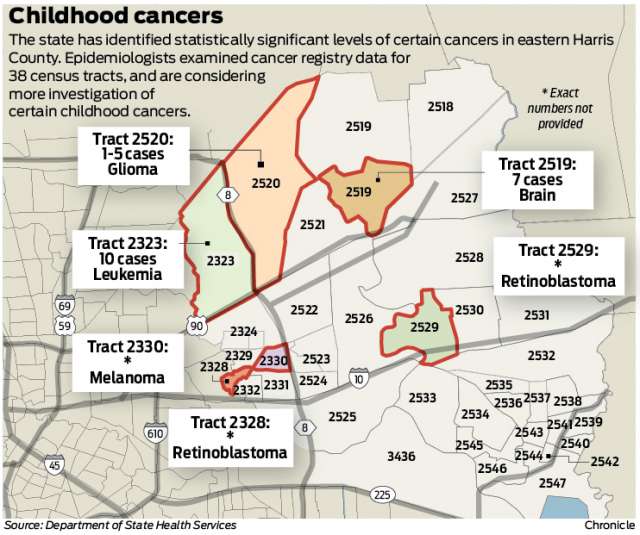

In certain census tracts, the report found much higher-than-expected levels of childhood cancers of the brain, skin and eyes, and of some kinds of adult cancers. In the entire study area, the report found unexpectedly high rates of childhood lymphoma and melanoma, and of brain cancer and cervical cancer for all ages.

One census tract had 16 times the statewide childhood rate for retinoblastoma, a cancer of the eye, while another tract had 14 times the statewide rate.

Census tract 2519 near Lake Houston had elevated levels of brain cancer. The state found 23 cases, where it expected to see 13.5. Seven cases involved children – around double the expected number.

Researchers found elevated childhood glioma — brain stem cancer — in a census tract north of U.S. Route 90 and east of Texas 8. A nearby census tract, 2323, had double the expected number of childhood leukemia cases.

San Jacinto Waste Pits (in Houston area):

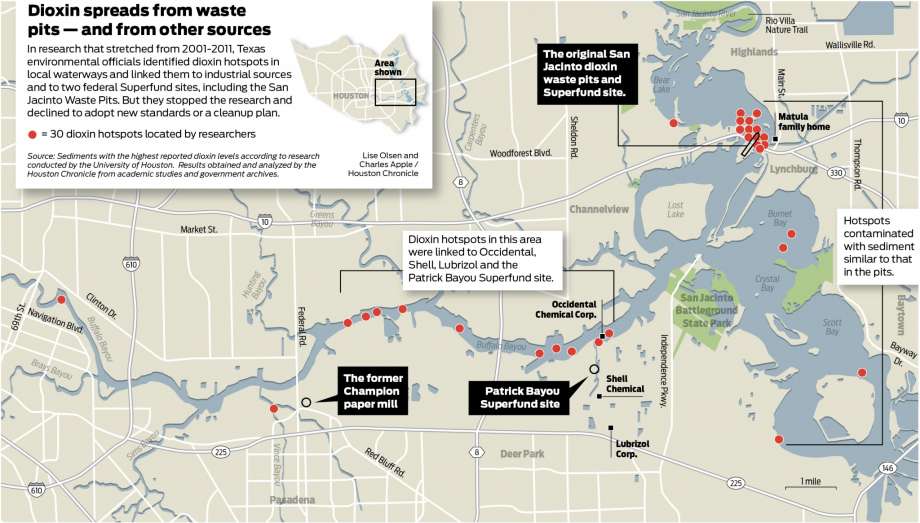

One particularly problematic toxic waste site is the San Jacinto waste pits, where a paper company had dumped tons of paper mill waste 50 years ago. For a half-century, the sludge was slowly seeping into the soil and water of eastern Harris County. The sludge contaminated the soil and rivers with dioxin, a deadly carcinogen. The pits used to sit on the edge of the river, but became half submerged over the years. The residents — mostly lower-income black families — had been complaining about a spike in cancer rates for decades before any cancer cluster reports were published.

In 2015, a cancer cluster study found elevated levels of kidney cancer, cervical cancer and childhood eye cancer — retinoblastoma — in census tract 2529, a town near the waste pits.

When the county and statewide commission on Environmental Quality sued the paper company in 2014, the paper company was found not liable to pay large penalties for the damage it caused.

After Hurricane Ike in 2008, storm surge was 12 feet at the waste pits. Immediately after Hurricane Harvey in 2017, the pits leaked toxic substances into the river. Tests showed that dioxin levels had spiked and were registering at more than 70,000 parts per trillion. (The EPA mandates cleanups for 30 parts per trillion and up.)

Existing minority neighborhoods have commonly been targeted as locations for toxic waste sites, bulk gasoline storage tank farms, sewage treatment plants, municipal landfills and illegal dumps, incinerators, concrete batch mix plants, animal rendering plants, metal fabrication & die casting plants, chromium plating plants, and smelters. This has resulted in these communities facing an unequal exposure to pollutants and consequent adverse health impacts.

Environmental Injustice — Disproportionate Risks for Low-income People of Color in Houston:

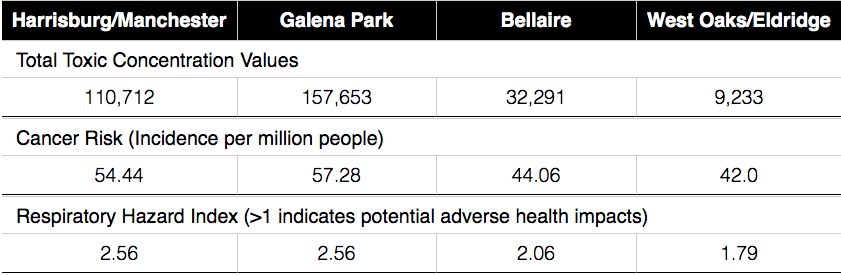

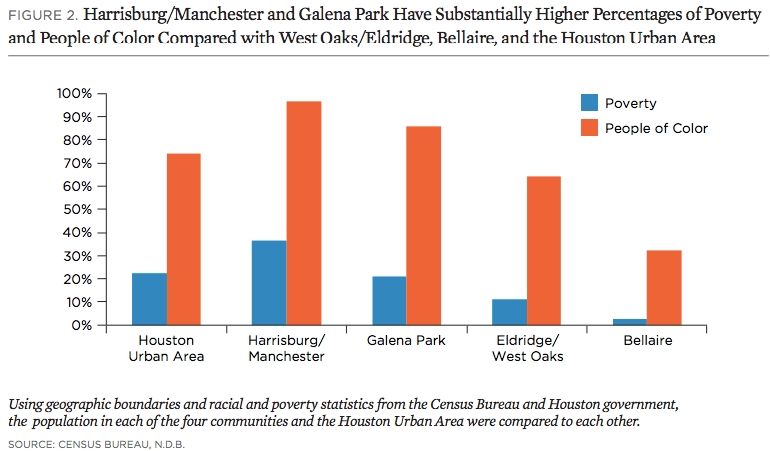

In 2016, the Union of Concerned Scientists and Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services released Double Jeopardy in Houston, a report finding that Houston-area communities with higher populations of color and higher poverty levels face higher risks from chemical accidents and everyday toxic exposure.

The report compared environmental risks and health impacts for two East Houston communities (primarily consisting of low-income people of color) to two more affluent, whiter West Houston communities.

The region most exposed to from toxic carcinogens was Houston’s Manchester neighborhood, home to roughly 3,000 people. It is surrounded by an oil refinery; a chemical plant; 21 Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) reporting facilities, 11 large quantity generators of hazardous waste; 4 facilities that treat, store or dispose of hazardous waste; 9 major dischargers of air pollutants; and 8 major stormwater discharging facilities. Approximately 90% of residents live within one mile of a hazardous chemical facility. It is 83 percent Hispanic and 14% black, 90% low-income, and the poverty rate is 37%. Not surprisingly, the cancer risk for people living in Manchester and neighboring Harrisburg is 22 percent higher than that for the overall Houston area. The neighborhood’s only public green space, Hartman Park, is across the street from a chemical storage facility.

Climate Change Exacerbates Environmental Injustice:

Climate change can exacerbate existing systemic environmental injustice. When Hurricane Harvey dumped trillions of gallons of water across Houston, it also damaged several petrochemical facilities in low-income communities of color, sending millions of pounds of pollution into the air. The hurricane also damaged a protective cap placed on the San Jacinto waste pits, sending pounds of toxic sludge into the surrounding area. One storm-damaged refinery in Manchester released a plume of cancer-causing benzene into the neighborhood.

After Hurricane Harvey, the EPA found that 13 of the 41 Superfund sites in Texas hit by Harvey were flooded in the storm — many of which contained hazardous toxic sludge.

A warming world can pose a fatal threat to human health by increasing the number of “bad air” days and asthma attacks, which are particularly common in cities polluted by industrial activity. In addition to heightening the frequency of extreme heat events, climate change enhances conditions that lead to the formation of ground-level ozone, or smog, the lung-burning pollutant that can trigger asthma attacks.

Dallas: A Few Environmental Injustice Cases

Toxic Lead in Dallas Soil:

From the 1930s to 1984, a corporation operated a notorious lead car-battery smelter in west Dallas, one of the few sections of the city where black people could live in the segregated post-World War II era. Today, west Dallas remains mainly inhabited by minorities. For decades, truck drivers hauling waste away from the smelter offered cash to the low-income people living nearby in exchange for letting the battery waste be dumped in their yards. In the 1990s, after a congressional investigation, the EPA declared the surrounding land a superfund site and dug out contaminated soil from 431 homes. The EPA said the clean-up was complete by 1995, but in the two decades that followed, residents have continued to find substances resembling battery chips on their property, a sign that the EPA didn’t dig deep enough when cleaning out the soil.

Contamination from an Electroplating Facility in Dallas:

Since the 1950s, an electroplating facility called Lane Plating Works had operated in Southern Dallas applying metal coatings to car bumpers and the like, using toxic metals including arsenic, cadmium, cyanide, chromium, lead and mercury — substances that cause cancer and damage the brain, kidneys and liver, as well as digestive, reproductive and nervous systems. In 2015, it declared bankruptcy, after which many records of their toxic chemical production were difficult to find. In 2018, it was declared a superfund site for contamination of nearby soil, wetlands, and groundwater, and the EPA held a meeting with local community members to discuss these risks. The EPA declined the residents’ most urgent concern — health impacts of the site’s toxins — claiming that they only test for contaminant levels, not health effects. Much of the surrounding remains contaminated, although little research has been released about health impacts from this contamination.